In Lesson 11, we talked about the Rule of Symmetry. What I said in Lesson 11 was that if something looks symmetrical, don’t mess with it. Perhaps a better way to state it is that at least try shooting symmetrically along with applying other framing techniques because it might look really cool.

Merriam-Webster offers this as the first definition of symmetry: “balanced proportions; also : beauty of form arising from balanced proportions.” Research bears out that all cultures find people with more symmetrical faces more beautiful; therefore, it seems logical that we might also find symmetrical photos beautiful. Oddly, this is less true than you might think. For example, placing a non-symmetrical subject dead-center in the frame does not make it more beautiful.

However, there are many subjects that offer themselves up and beg to be shot symmetrically. Let’s revisit some of the examples I used in Lesson 11 and compare how they look symmetrically vs using the rule of thirds. I’ve cropped the originally symmetrical photo into a rule-of-thirds photo to show how the symmetrical version works better.

Moon shot (DSLR photo):

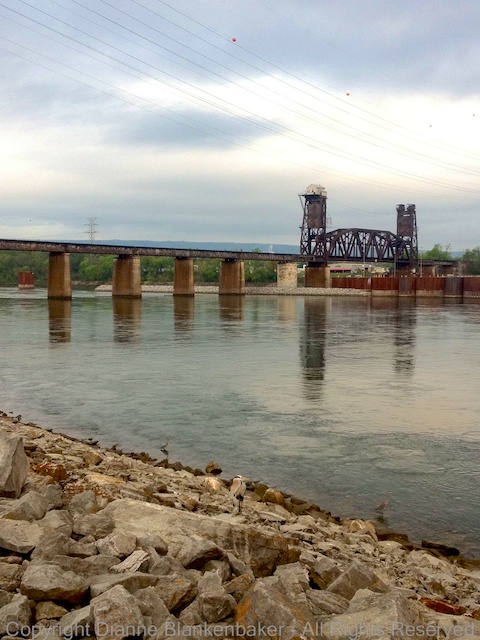

Bridge (iPhone 4S with Hipstamatic D-type film and Helga Viking lens):

Madrid Courtyard (iPhone 4S with Camera Awesome)–as a side note, this is a really bad photo that I should just delete, but it’s come in handy for lessons and it does work better symmetrically:

Now that you hopefully see that sometimes subjects just work better symmetrically, let’s take a look at a bunch of other symmetrical examples. Unfortunately, most of these were taken with a DSLR, but I’ve noted in the captions if they are iPhone photos. The point is that many subjects work well symmetrically. They might also work well using other framing, but symmetry is a great rule to apply as an option.

Your Assignment: Try cropping copies of your rule-of-thirds (or other) photos into symmetrical photos. Can you find some subjects that work particularly well in symmetry? Now go out and shoot. Look for opportunities to try out this framing technique. Hint: using the level in Camera Awesome can help you get better symmetry, particularly when shooting architectural subjects.