OK, I made this one up. But, as someone who has missed many, many moments when I saw a great photo op, I think it’s worth talking about. The rule of opportunity is: Get the shot! (within reason–I do no advocate harming others, wildlife, natural habitat, property, your iPhone, or yourself.)

I am personally haunted by many missed moments. One of the realities of photography you must accept is that each moment is its own. It doesn’t happen twice. If you think you’ve recreated the same moment, you probably aren’t paying attention to details.

There’s an old adage of photography that “the best camera is the one you have with you,” which is a paraphrase of the original quote from Barry Staver, a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer.

That is the power of the iPhone–you have it with you. But having your iPhone with you is only the first step in getting those moments that happen unplanned. As someone who has a long, complicated password on my iPhone, I have frequently missed shots trying to unlock my phone so I could get to the app I wanted.

The first strategy for making sure you can capture moments is to know ahead of time what to do. If you, like me, cannot unlock your iPhone in fewer than 3 attempts, repeat this mantra: “ The default app is the best choice when an opportunity presents itself.” I say this because it’s the only camera app that can be launched while the phone is locked (which is something I would love Apple to fix).

With the advent of iOS7, if you upgraded this week like I did, this is a good time to re-familiarize yourself with the Apple camera app. It looks quite different!

The camera icon blends with my wallpaper; swiping upward on it opens the camera app

Fortunately for the quick draw, the app still defaults to the camera mode, but you might want to practice swiping to pano mode for rainbows

I suggest turning off the HDR setting if it’s on so that, if you’re in a hurry, you will be ready to shoot. The point is to know how you are going to capture a moment that presents itself before it disappears.

Here are some moments that I barely caught (all of which I can list a bunch of things I wish were better about them) because I had a camera ready:

While shooting a parade for a local paper, I spotted this sleepy guy on dad’s shoulders–I had to run ahead of them to get this shot and couldn’t get back far enough for the framing I wanted. (DSLR)

Beams of light (or in this case a shadow) in the sky often don’t last long–you have to be quick to catch them. (iPhone 4S)

I was out shooting with my iPhone 4S when I spotted this spider. It held still just long enough–then it started running up the web towards me

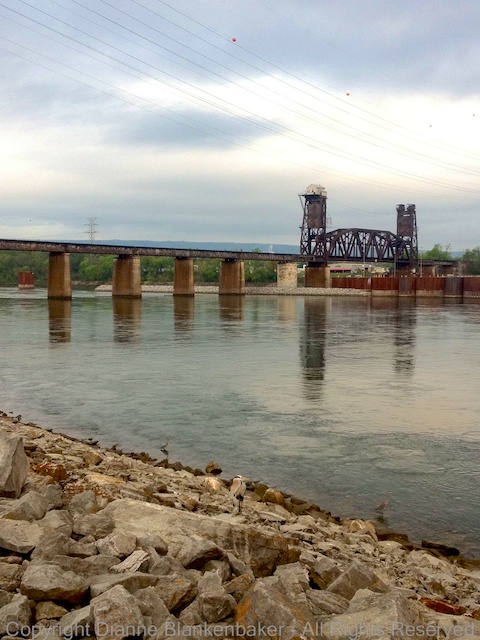

I hopped off my bike and grabbed my iPhone for this shot

During dinner at a restaurant on the French Riviera, I just happened to catch this with my iPhone 4S

While waiting for a train in Nice, I grabbed this shot with my iPhone 4S.

Rainbows are so unpredictable. You don’t know when they will appear or how long they will last. iPhone 4S panoramic.

The last bit of sunset with the moon barely in the frame. iPhone 4S panoramic.

Who hasn’t seen great clouds from a plane window? Sunrise over Madrid–iPhone 4S.

Another parade shoot and another run to get ahead of the local ballet group’s performance. (DSLR)

Capturing my husband seeing himself in an ad with my iPhone 4S.

The tiny boy wearing a cape in front of a giant cloud made me stop and shoot while out for a walk with my dog and DSLR.

Sometimes a moment presents itself that lasts longer than a moment. For example, dogs present endless passing moments (many which I’ve missed), but they also do cute stuff when they’re relaxing. Here are some examples of dog silliness:

One a quick walk to a local nature preserve, my dog got hot and decided to wallow in the mud. iPhone 4S.

My dog demonstrating some confusion about the proper use of pillows. iPhone 4S.

Here my dog seems to have the hang of pillows. (iPhone 4S)

Keeping warm on a cold winter evening. iPhone 4S.

A misinterpretation of the blanket protecting the couch. iPhone 4S.

Daddy makes a good pillow. iPhone 4S.

Taking a roll during a stroll. iPhone 4S (Hipstamatic).

Sharing toys with a visiting friend. iPhone 4S.

Of course Moose has to go, too. iPhone 4S.

Sharing the sofa. iPhone 4S.

Giant leap. DSLR.

Good scratcher. DSLR.

One of the important lessons of being a better photographer is to think like a professional photographer. Recognizing an opportunity to grab a shot is an important step. Ironically, if you don’t recognize the opportunity, you will never kick yourself for having missed it. But once you start looking at the world as a series of photo ops, you’ll want to be a quick-draw with your phone so you don’t miss them.

Your Assignment: Practice swiping upward on the camera icon on your iPhone lock screen to open your camera app. This may seem silly, but the way you access it changed a few updates ago from tapping the icon to swiping it upward, so you’ll want to make sure you have the feel of it. Take a few photos with the default app.

Remember that you can only set focus and exposure together in this app (unlike Camera Awesome, which we’ve been using for many lessons). Remind yourself that you’re going to have to make more compromises between the focus you want and the exposure you want if you need to capture a moment quickly and don’t have time to unlock your phone.

Experiment with choosing different focus/exposure points to get a sense of how much you can keep in focus and how much you can have exposed correctly using this app. The only thing more depressing than not getting a photo at all is getting one that fails to capture the subject–something in human nature prevents us from deleting that one bad photo of that one incredible moment and leaves us to torture ourselves with our failure every time we see it.