All right, DSLR owners. I’ve had so many people ask me this summer about back-button focus and how and why to use it that I thought it would make a good post. Since this is (as usual) a long post, let me just summarize by saying if you don’t understand “focus-and-recompose,” focusing modes, focus selection points, critical focus, the focal plane, depth of field, and how to control all of these things, you probably should worry about those before you worry about using the back button to find focus. Back-button focusing is a great tool to achieve better control over autofocusing, but if you don’t understand how to control focus and what settings and techniques allow you to do that with autofocus now, it’s really not going to make a big difference for you.

That said, here goes my explanation of what back-button focusing is, why I use it, and some pointers on how to enable it on your camera if you want to give it a whirl.

First, what the heck are people talking about?

Back button focus means using a button on the back of your camera body to autofocus instead of autofocusing when you half-press/press the shutter button.

Why would you want to do that?

By separating autofocus from the button that also releases the shutter, you gain complete control over when your camera is focusing and when it isn’t, you can stop switching between autofocus modes and leave your camera in continuous focusing mode, and you make it easier to avoid releasing the shutter when you don’t mean to.

Why wouldn’t you want to do that?

Well, personally, I think back-button focusing is the bomb and I’ve been using it for so many years that it’s the first setting I adjust when I buy a new camera body because I can’t handle focusing via the shutter button.

That said, I have one big caution for you when it comes to switching to back-button focusing: choose when to make the switch cautiously. Your brain is programed to believe that the shutter button autofocuses right now. If you switch to back button, you will need to practice daily for about 2 weeks (depending on the neuroplasticity of your particular brain) to retrain yourself to go for the back button to find focus before you press the shutter. You would not want to make the switch and then go on the once-in-a-lifetime trip and/or to a once-in-a-lifetime event without having taught yourself this new habit before you get there–you will forget to focus and make a bunch of blurry photos at first.

Also, because of this need to create an unconscious habit, you don’t want to switch back and forth between using the back button technique vs the shutter button–you will get yourself very confused.

I Don’t Get It–Why is Back-Button Better?

In spite of all the hype about back-button focusing, a lot of students don’t get it at first. They look at me puzzled and try to understand why they would care which button causes the camera to focus.

So, let me tell you a little story about why I was so enthused when I learned about back-button focusing.

Back when DSLR screens weren’t so big or bright, I was doing a lot of landscape photography on a tripod. I found manual focus to be extremely difficult because the viewfinder focusing screen was terrible and I hadn’t yet invested in a loupe for my LCD screen, so I couldn’t see if I was in focus in daylight. So, I would put my camera on the tripod, compose my image, and then decide where I should focus based on DOF and hyperfocal distance. Then, I would begin the struggle of turning the camera to point at the place where I wanted to focus, hold the shutter button halfway, and then try to recompose the image back to what I wanted without releasing the shutter. I invariably either took the shot while still adjusting or lifted my finger and my focus unlocked. When you lose focus lock and then press the shutter button again, the camera re-focuses on whatever it picks to focus on instead of where you want to focus.

I then discovered there is a little focus lock button on Canon’s that if you press it, focus will remained locked “for a few seconds” giving you an unspecified amount of time to reset and shoot before it turns off. This little button just stressed me out because I was racing against a clock and I didn’t know how much time I actually had before the focus would unlock.

Then, I learned about back button focus. And, ahhhh, breathed a sigh of relief. I could still autofocus, but once I found focus with the back button, I was free to move the camera with both hands for as long as I wanted until I was ready and could get the shot I wanted. And so my love of back-button focusing was born.

If you’re not using autofocus on a tripod a lot (Manual focus avoids this problem), you will not have the same appreciation for this struggle. That doesn’t mean back-button focusing doesn’t still have many advantages.

By the way, even though I now have the tools to manually focus on a tripod, my lenses allow full time manual focus, meaning I can manually focus even when the lens is set to AF. By using back-button focus, I can leave my lenses on AF at all times and I don’t have to worry about undoing my manual focus when I press the shutter button.

I’m Not Autofocusing on a Tripod–Why Would I Care?

A big reason it can be hard to grasp why back-button focusing is so powerful is if you haven’t spent much time working on gaining control over focus in general. If you’re going around autofocusing with all your selection points turned on in single focus/one-shot focus mode (or if this sounds like gibberish to you), you actually have no idea where you are focusing. If you have no idea where you are focusing, back-button focusing probably isn’t the first step you need to take to get control of focus.

Personally, I have 3 bodies that have 61 focus selection points. Those 61 focus selection points are handy when I’m trying to get a shot of, say, a Cliff Swallow in flight. It’s a tiny bird that swoops and dives erratically and I cannot pan with it well enough to keep it in focus using my normal technique. As such, those 61 focus points become very handy when the bird is against a sky or other background that doesn’t fool my camera into focusing on the background (and I’m in continuous focusing mode and I have tracking set properly for such a subject).

The rest of the time, I use either 1 or 9 focus selection points. If I’m shooting landscape, portraits, etc, I use 1 focus selection point. If I am shooting moving subjects like birds that aren’t as erratic or small as swallows but are likely to fly, I turn on focus point expansion that allows me to find focus using the center point, but will activate the surrounding 8 points if the subject moves to help keep the subject in focus.

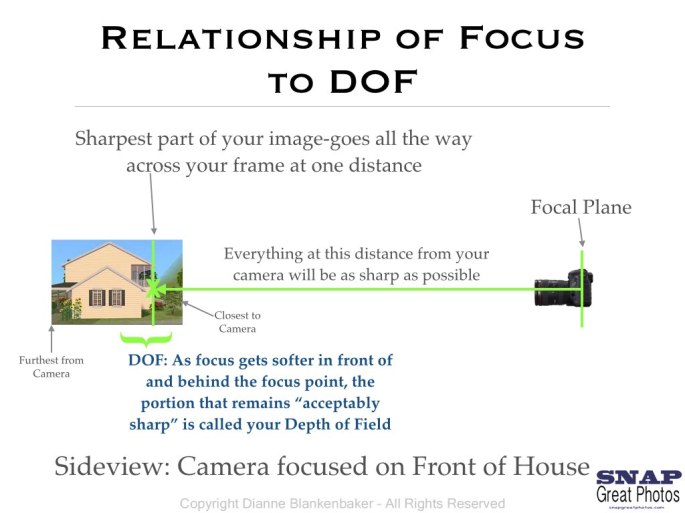

Now, this is about when students ask, “But I want more than one thing in focus. How am I supposed to get multiple people in focus if I only find focus in one place?” Well, I have news for you: critical focus only occurs at one distance from the camera. If 4 focus points light up when you press the button, it’s because the camera thinks all four of those things are the same distance away. If you want multiple people in focus, you need to understand DOF. This is the diagram I use to explain the relationship between where you find focus and how DOF keeps more than that distance sharp to students:

So, first understand how focus works and how DOF helps you get what you want sharp, then worry about whether you should be using the back button to find focus or not.

Once you are very clear on what the focal plane is (which is technically where your camera sensor is positioned in your camera body, but is also often used to mean the plane of critical focus in the scene/subject you are shooting) and how to control DOF, you will realize the advantage of using one focus selection point whenever possible: it let’s you decide what should be sharpest in your image instead of your camera.

All of the Images in this Gallery Used the Focus-and-Recompose Technique (All of my Images are Made Using Back-Button Focusing)

Once you make the switch to using only one focus selection point, you then will want to make a lot of use of “focus-and-recompose,” which is what I was doing in the tripod example. However, focus-and-recompose is a fundamental technique whether you’re on a tripod or hand-holding. It allows you to get both the focus you want and the composition you want without being dependent on a focus selection point being in the right place (if you are in one shot/single focusing mode). It means that, for example, you can use the center focus selection point (which always has the greatest ability to focus the most precisely in all cameras) to autofocus on a subject’s eyes and then lock focus and recompose so that your subject is artistically framed in your image. It gives you the ability to control critical focus without losing control over composition. The key is to ensure that when you recompose, you don’t change your distance from the subject as this will cause focus to shift forward or backward based on your movement.

The other key is that if you recompose, you must hold the focus. And this is where back-button focus becomes a life saver. If you have to half-press the shutter and hold it while you shift, you may either accidentally press the shutter all the way or let go of the shutter all together. Then you have to start over. With the back button, you can simply press the back button to find focus, release, and then concentrate on recomposing. When you press the shutter, because you have turned off focusing on the shutter button, your focus does not change and, as long as you also haven’t changed the distance from you to the subject, their eyes will be the sharpest thing in the image even though the focus selection point is no where near their eyes when you eventually do press the shutter button.

There are also advantages to using back button focusing when you are continuously focusing (AF-C on Nikon, AI Servo on Canon). As you track a subject in motion, you hold the back button and it keeps focusing, giving you more control on when you focus vs fire (it can be challenging to pan while holding the shutter button half way without firing). If the subject stops, you can release the back button, locking focus as if you were in one-shot/single mode and fire away. Essentially, you gain total control over when the camera is autofocusing and when it is not. It’s a beautiful thing once it clicks in your head how much easier it is to control focus this way.

This also means you never have to switch between one-shot/single focusing mode and continuous focusing mode–if you’re not pressing the back button, your focus is locked regardless of which focusing mode you’re in. By comparison, when you use the half-press of the shutter to focus, if you’re in continuous focusing, it keeps refocusing until the shutter releases, meaning it’s not possible to focus-and-recompose.

To summarize, back-button focusing is an advantage in all situations. There are fewer settings you have to use to control focus when you back-button focus and you gain greater control with less coordination. I honestly cannot think of any reason not to switch to back-button focusing other than ensuring you have the time to develop the habit before you make the switch.

You Convinced Me–Now What?

Remember, if you make the switch, you will forget to focus at first. Do not, say, decide you are going to make the switch because you are shooting a wedding tomorrow and you want to give it a try. Make the switch and really pay attention to whether you are finding focus when and where you want until you find yourself automatically pushing the back button without thinking about it and getting the results you want. Then, you can go shoot a wedding with back-button focus. 🙂

Now, the remaining question is, how do you turn it on/disable the shutter button focus? This requires finding the setting in your manual (which is usually different for each camera) that will allow you to assign functions to your buttons. You will, unfortunately, not find anything called “back-button focusing” in your manual.

In Canons, these settings are in the custom function menus and are pretty obtuse. Once you find a setting for the shutter button in custom controls, set it for “Metering Start” (or another setting that doesn’t include anything with AF in it) which will disable focusing with the shutter button. Find the settings for the AF-On button (the button is in upper right corner of camera back and furthest to the left of those 3 buttons—very convenient to find with your thumb once you get used to it). Make sure the AF-On button is set to “Metering and AF Start.”

In Nikons, it’s even more obtuse, but I don’t look at Nikons every day, so maybe it makes more sense to a Nikon shooter. In any case, you also need to go to the custom setting menu, to controls, and then go to assign AE-L/AF-L button. Choose AF-On from that menu. If the shutter button is also in that menu, check to make sure it isn’t enabled for AF-On as well. I’ve been told that in many Nikons you also need to set the camera so that the camera will still fire if it hasn’t been focused in order to get it to fire when it doesn’t know that you don’t want to refocus. That setting is also in the Custom Setting Menus under Autofocus and you want to set AF-C and AF-S priority selection to “release.”

Now, go practice, practice, practice! 🙂