Today’s lesson is about focus. Focus is usually one of the few inescapable rules of good photos. Although, even as I write that, I think of the photo of Paul Simonon of the Clash smashing his bass on stage. The photographer, Pennie Smith, reportedly didn’t want the photo to be used because it wasn’t sharply focused. It graced the cover of the London Calling album anyway and is considered by many to be one of the most iconic photos in rock and roll.

However, the vast majority of the time, photos fail when the subject isn’t sharp. With the iPhone, sometimes this gets a little tricky, but it’s easily solved.

Let’s say you see something and you pull your phone out of your pocket, launch the camera app and snap a shot as quickly as possible. Your iPhone camera will decide what the subject is. Sometimes it’s quite good at this (like people’s faces). Sometimes it’s not.

To demonstrate this, I’ve lined up 3 things in a row that runs from close to the camera to far from the camera. To maximize the difference the focus point can make, in the image on the left, I focused on the Cetaphil bottle in the foreground. In the image on the right, I focused on my dog. (Click on the image to get a larger view.)

Notice the difference in how sharp the letters on the bottle are and my dog is in the background in the first image versus the second. If I would have let the iPhone choose where to focus, it would have focused in the middle, resulting in an image with slightly soft focus in both the foreground and the background. Instead, I can choose which part of the image I want to be sharp.

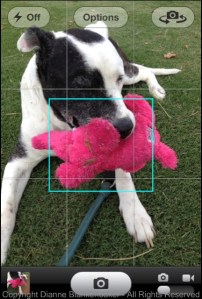

To choose what you want to focus on, touch the screen on the thing you most want to be sharp. To demonstrate this, I did a screen capture of the iPhone camera and drew in a square approximating what the focus box looks like. In this image, this is where the iPhone wanted to focus by default:

In the next image, I touched the screen to tell the iPhone to focus on my dog’s eye. That made the elephant slightly softer in focus, but the elephant and my dog’s eye are close enough together that it’s hard to see the difference except under magnification. The key is that my dog is the more important subject, and his eyes are the most important things to have in focus.

One of the things that can be an advantage with an iPhone or any small-sensor camera is that they tend to keep a lot more things in focus from the front to back of the subject you’re photographing than a bigger, fancier camera. This is also a disadvantage, but we’ll save that for a later lesson.

As a side note, when you touch the screen to set the focus point, the iPhone default camera app also uses that point to set the exposure. We’ll talk more about exposure in tomorrow’s lesson.

Your assignment: Practice taking photos of several different subjects in different settings. Wait to take the picture until the focusing square appears. Notice what the iPhone (or other camera) is picking for you. Take a second photo of each subject and choose what you want to focus on. Pick the thing that is most important to you to have in focus (hint: eyes are always a good choice if your subject has them). Now look at the photos on a large computer screen you can see well. Take a look at what’s in focus. Where does the iPhone’s automatic focusing decision work well? When do you notice a big difference between what it chose and what you chose?